In the course of reading an interesting article by Andrew Crumey, ‘The Sun Does Not Rise‘, about science, religion, and magical thinking I learned an interesting ‘fact’. The scare quotes are just because I only have Crumey’s word for it. For what?

How many colours are there in the rainbow? My answer was seven: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. Apparently, before Newton’s work on optics the man in the street would have said 5. Moreover Newton’s addition of orange and indigo were the result of theoretical commitments rather than observation:

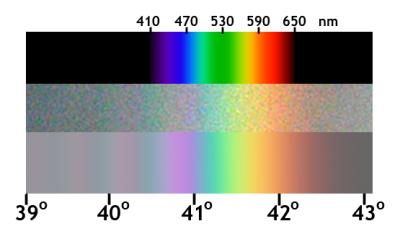

Newton’s wrong guesses are, however, as interesting as his correct ones. A well-known example is his conviction that light is made of particles, not waves. What he had in mind were solid ‘corpuscles’, not the photons of modern physics, but it’s still tempting to see him as having been half right. And in trying to explain the splitting of white light into a spectrum, he came up with the beautiful notion that the width of the coloured bands matches the mathematical proportions of a musical scale. People had traditionally counted no more than five colours in a rainbow, but for his theory to work Newton needed more, so he introduced two ‘semitones’, orange and indigo, and we’ve been counting seven colours in a rainbow ever since. Generations of schoolchildren have learned mnemonics that colour-code light, such as ‘Richard Of York Gave Battle In Vain’, which have as much to do with physical reality as the signs of the zodiac.

Newton’s harmonious vision was a fossil from a very deep layer of intellectual history: the doctrines of the semi-legendary Pythagoras who, apart from discovering that theorem about the square on the hypotenuse, supposedly also had a leg made of gold and could appear in two different places at once. The Pythagorean view that ‘all is number’, and that the motion of the planets was linked to musical principles (the ‘harmony of the spheres’), was also endorsed by the German mathematician Johannes Kepler, whose Harmonices Mundi (‘The Harmony of the World’, 1619) tried to explain the solar system in terms of music and geometry, and correctly proposed what we now call Kepler’s third law of planetary motion.

There’s plenty more in this vein.